MASS IN C MAJOR, K258

INTRODUCTION

Watermark evidence places “K258” in December, 1775. It is scored for two oboes (added later), two trumpets in C, timpani, violins, bass, organ continuo, and three trombones doubling the alto, tenor, and bass vocal parts. As in “K220”, the brevity again conforms to Colloredo’s requirements and the scoring to his tastes. First performance is unknown, but the archbishop’s criteria strongly suggest the cathedral in his presence.

KYRIE

Whoever said Mozart’s Salzburg masses were lightweight, conventional works never looked into the Kyrie of this mass. In 2003, my initial notes indicated I had listened to its two minutes of music sixty or seventy times and I was still guessing as to what was going on.

I am in 2014 up to twice that number and now know enough to share with you some preliminary thoughts.

By turns the music is festive or dramatic, mostly but not always sung by the chorus, and then lyrical and tender, mostly but not always sung by the soloists; mostly but not always Type I; and all in a moderate triple time without pauses.

As with so many movements of Mozart’s masses, there are several different ways of looking at the structure.

The broadest view reveals five groups of “Kyrie eleison” by the chorus separated by four of “Christe eleison” by the soloists. We’ve seen three textual divisions in a Kyrie, five divisions, seven divisions, overlapping divisions, but never before nine divisions. Furthermore, they don’t group into musically coherent sections.

There are eight brief themes, each expressing a single individual musical statement. Each is exactly twelve beats long—four repetitions of the triple-time unit. Six themes repeat in some form, but no repetition is exactly the same as any other.

These themes populate seventeen brief subsections. Each subsection contains exactly one theme and thus is twelve beats long—except that one subsection contains shortened versions of two themes and is eighteen beats long and one subsection contains a shortened version of one theme and is six beats long. Fear not, all will become clear.

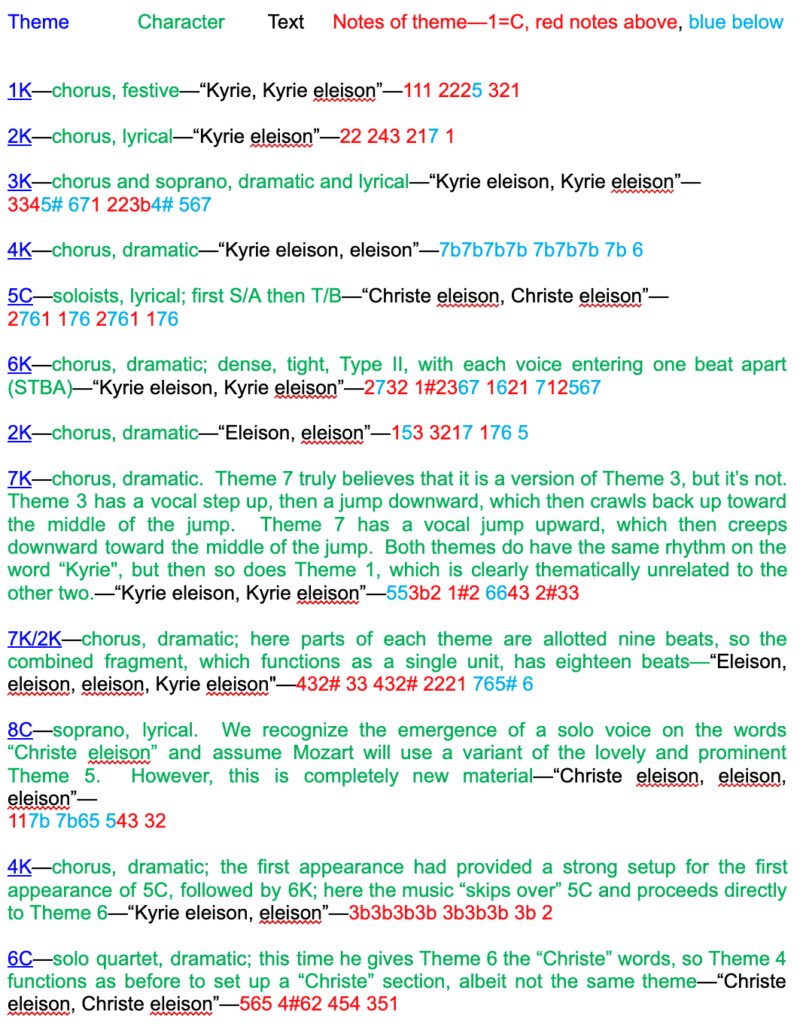

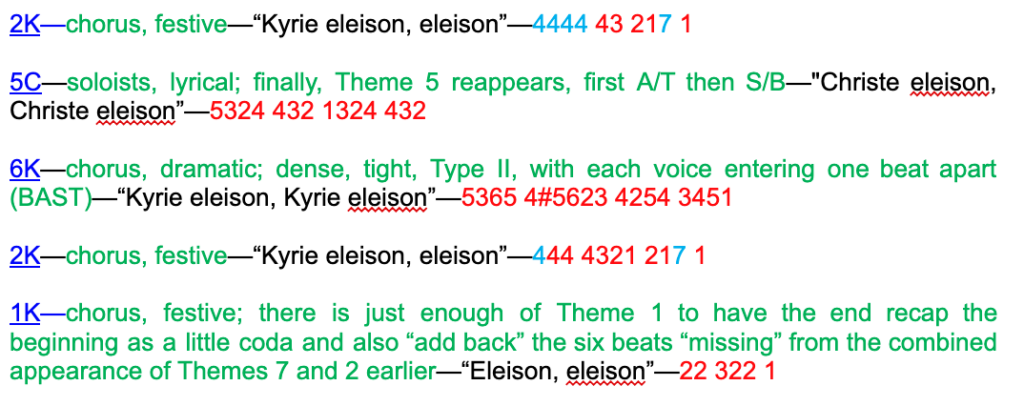

The convention below for the subsections is the theme number followed by whether the text is “Kyrie eleison” (K) or “Christe eleison” (C):

For ease in clicking around through the various snippets, here they are on one line:

1K 2K 3K 4K 5C 6K 2K 7K 7K/2K(18 beats) 8C 4K 6C 2K 5C 6K 2K 1K(6 beats)

Of the thirteen themes beginning “Kyrie” subsections, 1K appears twice, 2K four times, 3K once, 4K twice, 6K twice, and 7K twice. Of the four themes beginning “Christe” subsections, 5C appears twice, 6C once, and 8C once. Theme 6 thus appears with both texts.

If we try to listen for nine musically coherent sections beginning K-C-K-C-K-C-K-C-K, it rapidly becomes a muddle, as the music just doesn’t divide that way, and there’s way more “Kyrie” than “Christe”.

But if we don’t try to force our ears into “Kyrie” and “Christe” groups, we will notice that 2K, in all its forms, is the only theme that ends in a clear cadence. We can then form five satisfying sections with a mixture of words all ending in 2K:

1K 2K—3K 4K 5C 6K 2K—7K 7K/2K—8C 4K 6C 2K—5C 6K 2K 1K(coda)

Or, with just a little fussing, if we call the first 2K incidental and say that the first section ends at 4K instead, there is a dramatic transition into a lyrical start at 5C to a phrase which can actually be said to repeat later, with another lyrical start at 8C in between—and all three starting with “Christe” and ending with 2K:

1K 2K 3K 4K—5C 6K 2K—7K 7K/2K—8C 4K 6C 2K—5C 6K 2K 1K(coda)

I’m sure there must be other ways to organize the sound mentally, but whether we listen in musical groups or just take the movement in one continuous sweep, the amazing thing is how well the themes fit together without wasting a note, including the “adding back” of the “missing notes” at the end.

The seamlessness of these odd, slightly different little fragments makes me wonder if Mozart knew anything of jigsaw puzzles.

During the family’s Grand Tour when Wolfgang was a child, the Mozarts were in residence in London between April, 1764, and July, 1765. Brother and sister performed three times for King George III and Queen Charlotte. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that among the gifts from the court might have been a “dissected map”, an expensive educational toy then all the rage in London. This was a map painted onto wood and carefully cut into curved pieces by a jigsaw, invented and marketed from about 1760 by John Spilsbury, a mapmaker and engraver who just happened to be apprentice to Thomas Jefferys, the King’s Royal Cartographer.

The queen, who had grown up in a quiet North German duchy to ensure her virginity, was only nineteen at the time and had been in England only two years. She was still learning English, so she herself could have been introduced to the new toy as part of her own orientation to England.

A set of six sonatas by Wolfgang for keyboard and flute or violin, “K10”-“K15″, was published in London and dedicated to the queen, and who knows who that engraver might have been?

We know that Mozart loved games of all sorts, including puns, anagrams, codes, riddles, number games, card games, and billiards. He played and may have invented a game in which throws of two dice determined what measures of music from a table would be used to make a minuet.

I can imagine him pushing around on his composing table scraps of music paper bearing each slightly differently shaped theme of this Kyrie, trying them in different places to see how they might fit together.

GLORIA

The pace continues in brisk and bracing duple-time as Mozart crams the entire Gloria into a space only about thirty seconds longer than the Kyrie. There are no pauses and the pace never slows. No puzzles here; the performers must sing fast and articulate clearly against a frenetic and insistent orchestral background. Actually, I’d like to get a violinist’s opinion someday about the music, which seems to have no particular merit but to keep up a relentless pace.

Each of the seven straightforward sections has its own exuberant and tuneful themes: “Gloria“, chorus; “Laudamus te“, soloists; “Gratias agimus“, chorus; “Domine Deus“, soloists; “Qui tollis“, chorus; “Quoniam“, chorus; and “Cum Sancto Spiritu“, chorus. The choral parts are all Type I except the last, which is Type II—not long, but enough perhaps to raise an archepiscopal eyebrow.

There are two other evanescent quirks which I take to be digs at the archbishop.

After a couple of lovely solo passages to start “Domine Deus”, there is a sudden flurry of dense Type II singing by the solo quartet. The soprano starts a new theme, the tenor discovers a countertheme, the alto jumps in with an imitation of the soprano, and the bass picks up the tenor’s theme. But Mozart slaps his own wrist—”No time! No time!”—and it’s gone in a flash.

As the next section, “Qui tollis”, hurtles on, Mozart intentionally has the chorus sound tongue-tied. I thought I was hearing sloppy choral singing at the word “Suscipe”, but discovered that the sound is the same on the other recordings as well. The score bears this out. First, the rhythmic length of “Suscipe” is different in three of the four vocal groups. Second, the sopranos start singing the syllable “sus-” a beat later than the others, who by then are singing “-pe”. And third, three of the four groups sing “-ci-” at slightly different times. All you can really hear is a lot of “sss” sound. Perhaps it sends the message, “See what happens when you make us sing too fast?”

There may be another quirk. At the very end, the orchestra reprise their music of the “Gloria” section and the chorus sing just enough of a hint of their opening theme to say, “I would have done more than a few notes if I’d only had the time”.

CREDO

The breakneck pace eases for the Credo and Mozart allows the music to spill over into nearly six minutes. Two faster outer sections in triple time, which share several themes, flank a slow section with unrelated music in duple time. The chorus do most of the singing in the outer sections; the soloists are prominently featured in the middle section.

The opening music for “Credo in unum Deum“, Theme 1, is a noble, joyous Type I folk hymn. It is fairly expansive and develops several ideas which will recur together. It ends with the word “invisibilium” and a brief orchestral break. There follows lovely but unrelated material at “Et in unum Dominum”, “Et ex Patre natum”, and “Deum de Deo”, which is worth developing but which we will not hear again.

`A shortened Theme 1 reappears at “Genitum, non factum“, followed immediately by Theme 2 at “Qui propter nos homines” and then Theme 3 at “Et propter nostram salutem“. A satisfying descending motif at “Descendit de caelis” brings the Christ child down from heaven and the section to a close.

“Et incarnatus est” is a tender song for tenor solo. Indeed, it almost makes me sorry that I dislike the tenor voice so much. “Crucifixus” has an unusual and arresting sound. The soprano, alto, and tenor soloists quietly sing the words while the whole bass section intone just the word “Crucifixus” repeatedly and slightly higher each time. I can imagine Christ’s followers huddled in a corner and talking among themselves while the Sadducees decree His execution.

To begin the third section, the chorus suddenly burst forth with an assertive ascending theme, almost an inversion of “Descendit”, and Christ and Theme 1 are resurrected. A variant of Theme 2 at “Et iterum venturus est” leads directly to Theme 3 at “Cum gloria judicare“. As usual, the music bows reverently for the word “Et mortuos” and, as we have often seen, the chorus repeat the word “non” in “Non erit finis“.

Up to this point in the mass, Mozart has really behaved admirably, with no-nonsense time management and lofty themes. However, he often has a trick up his sleeve for “Et in Spiritum Sanctum” and there is no exception here. The soprano and alto sing a lovely little song together accompanied by a prominent chirping sound in the violins. Indeed, the sound is so sprightly and infectious, I imagine the fiddle players actually standing up and dancing about (as I had previously imagined in the same section of “K140”).

Theme 1 returns at “Et unam sanctam catholicam“, followed by Theme 2 at “Et exspecto resurrectionem“, but not Theme 3. The music quiets once more for “Mortuorum“. There is one final piece of Theme 1 for “Et vitam venturi saeculi” followed by a brief and satisfying “Amen”.

SANCTUS

The no-nonsense “Sanctus” begins with bold, confident Type I chords giving way to a “Hosanna” part Type II and part Type I, all over in about a minute.

BENEDICTUS

“Benedictus” is structured as ten dramatic repetitions of the word “Benedictus” by the chorus separated by portions of the entire text sung by the soloists. This is reminiscent of the way the bass singers are set against three of the soloists in “Crucifixus” and provides a counterbalance to the sadness of “Crucifixus”. Here the followers of Christ not only express their joy at His everlasting life, but take the opportunity to showcase their singing as well. The chorus return with just the Type I portion of “Hosanna” for a buoyant conclusion.

AGNUS DEI

DONA NOBIS PACEM

Agnus Dei is both solemn and uplifting. It is also very nearly the longest movement of the mass. Mozart might have sung through what he had written so far, looked at one of the gold watches Leopold had bought in Geneva and offered for sale in Salzburg as gifts from various monarchs, and concluded that he had all the time in the world for a dreamy folk hymn where both chorus and soloists could meander through their best Type I stuff.

All three themes repeat, but instead of using different music as a separate movement for “Dona nobis pacem”, Mozart here includes it as an integral part of the Agnus Dei by using the same music so as to have no break in the quiet mood.

Theme 1, “Agnus Dei“, chorus

Theme 2, “Miserere“, solo quartet

Theme 3, “Miserere“, chorus

Theme 1, “Agnus Dei”, chorus

Theme 2, “Miserere”, solo quartet

Theme 1, “Agnus Dei”, chorus

Theme 2, “Dona nobis pacem”, solo quartet

Theme 3, “Dona nobis pacem”, chorus

A coda on “Dona nobis pacem” for solo quartet and chorus says a lush “Amen” musically, if not verbally. The Swiss watch must have stopped, as the fourteen repetitions of just two alternating chords is twice too long.

–06/19/2014

![]()