MASS IN G MAJOR, K49

INTRODUCTION

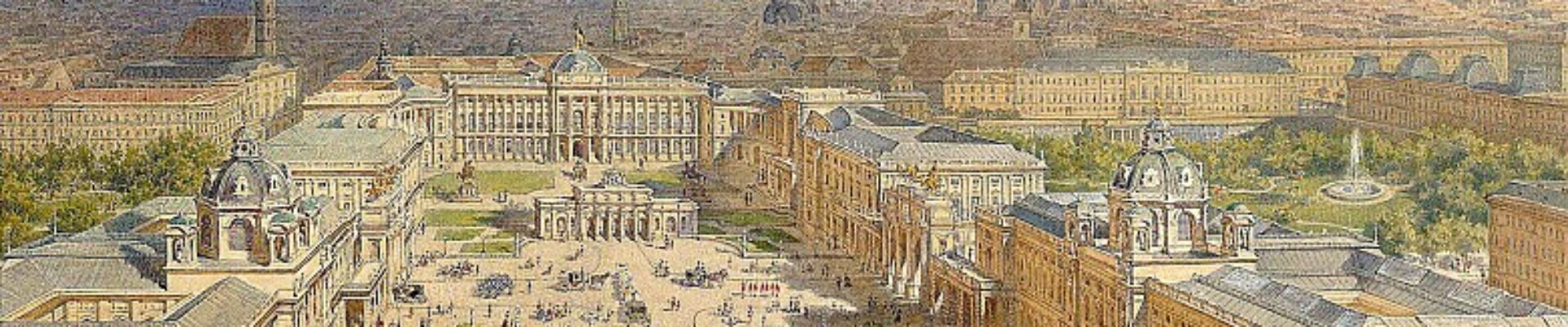

This mass was written in December, 1768, just after, and perhaps concurrently with, “K139”. The family were just about to return to Salzburg after a year in and around Vienna and Wolfgang would be expected to compose church music for Archbishop Schrattenbach. I can imagine Leopold telling him, “OK, you wrote a big one, now try a small one”.

If Wolfgang had a model for his short masses, I would probably look first to his father, as had been the case with the “K139” cantata mass. Leopold wrote some short masses, but none has been recorded to date.

Wolfgang would certainly also have been exposed from a tender age to the short masses of Eberlin, kapellmeister in Salzburg until his death in 1762, who left the scores of over three hundred masses, mostly short and in the old polyphonic style. Two short masses are recorded on CD, an A minor and a C major (years unknown). They are churchy, dense, and pretty boring, with Type II writing throughout. Large portions of the text overlap between voices for the sake of brevity (called telescoping or polytextuality) and the music of each movement sounds just like the music of every other movement. Nothing much stands out for young Mozart to take away (see the brief discussion in “Cantata Mass Trends, New Salzburg”). A bright spot in Eberlin is a very short “Missa Brevissima” in C major (year unknown), which is festive, lyrical, and folklike, available at this writing only on YouTube.

Michael Haydn wrote fourteen short masses before coming to Salzburg. “MH42” and “MH44” from about 1762 are recorded—gentle, accessible, folky, with brief solos and mostly Type I choruses with severely telescoped Gloria and Credo. In Salzburg, he wrote two short masses between 1763 and 1768, but they are not recorded.

It is conceivable that Mozart might have seen one or more of Joseph Haydn’s four short masses written prior to 1768. “H XXII 1” (1750) is gentle, tuneful, and folklike, with soprano solos and duets, Type I choruses, and telescoped Gloria and Credo (although the score was so long lost that Haydn himself rediscovered it only in 1805). “H XXII 3” (1750) is gentle, tuneful, folklike, with brief solos, Type I choruses, and telescoped Gloria and Credo. “H XXII 2” (fragment, 1768) is learned and churchy, with Type II choruses throughout and telescoped (partial) Gloria.

See the essay on “K65” for examples of polytextuality.

Maybe Mozart simply took his own freshly-written “K139” cantata mass as his model, keeping the accessible, folklike sound and compressing his favorite chunks of text down to musical theme fragments, especially in the long Gloria and Credo. The sections of the Gloria and Credo are clearly announced and the texts are not telescoped. Some of the themes are even linked to each other, an idea that he would develop as time went on.

“K49” is scored for violins, violas, basses, organ continuo, and three trombones doubling alto, tenor, and bass vocal parts. There is no record of it having been performed anywhere.

KYRIE

“Kyrie” begins with a quiet introduction by the chorus in duple time (Example 1), giving way to a swaying triple rhythm, with the words “Kyrie eleison” in the major mode (Example 2) and “Christe eleison” in the minor mode (Example 3). The voices imitate each other at an interval almost short enough to be an echo in church. Mozart does not use a traditional three-part structure, but alternates five brief sections: “Kyrie”—“Christe”—“Kyrie”—“Christe”—“Kyrie”.

GLORIA

The Gloria is through-composed as a sort of jolly march, with the words sung alternately by the chorus and various soloists. There are no pauses and the music only seems to slow down in places where the words are given longer note values. Always the orchestra maintains an insistent metronome-like beat, which makes us want to get up out of our seats and march around the church. However, the music does not all sound the same, as it would in Eberlin’s hands, but uses distinctive theme fragments for the portions of text whose sections in “K139” amounted to mini-movements, complete in themselves.

I should point out before we go any further that in “K139”, the first words of the Gloria, “Gloria in excelsis Deo”, are set for chorus, whereas in this mass, the priest (in recordings in the person of the solo tenor) intones them in Gregorian chant. The rules for this are extremely complicated and have to do with, among other things, the day of the week, the time of year, the festivity of the occasion, the number of priests and deacons officiating, whether fasting is involved, whether a “Te Deum” has been sung the same morning, and occasionally whether the priest’s robes are purple. Suffice it to say, if it was legal to have the chorus or a soloist sing these words in any given mass, Mozart would have written the music for them; otherwise, he started, as here, with the following text, “Et in terra pax”.

Sections sort out as follows: “Et in terra pax“, chorus; “Laudamus te“, soprano; “Gratias agimus“, chorus; “Domine Deus“, soloists in various combinations; “Qui tollis“, chorus (except for the first “Miserere” for soloists in various combinations); “Quoniam“, soprano; “Cum sancto spiritu“, Type II chorus.

The devious mind of Mozart can be seen here, even at age twelve, searching for a way to unify the music. The fragments that begin “Et in terra pax”, “Laudamus te”, “Quoniam”, and “Cum sancto spiritu” are all thematically related. Listen to the first five or six notes of each. The rhythms are different and there is an extra note here and there, but the jump up and the little turn are the same in all. “Laudamus te” and “Quoniam” both continue with notes similar to each other. “Et in terra pax” and “Cum sancto spiritu” continue on a different path, but also similar to each other.

CREDO

PATREM OMNIPOTENTEM

As with Gloria, the first words of this Credo are chanted, not sung. The first section of music, starting at “Patrem omnipotentem“, is set in triple time, mostly for Type I chorus, with “Visibilium omnium” being sung briefly by soprano solo and “Et in unum Dominum” by alto solo. The music continues without pause but with theme changes (this time unrelated to each other) demarcating “Et ex Patre natum”, “Genitum, non factum”, and “Qui propter nos homines”. The section concludes with the line “Descendit de caelis”, set to descending music.

ET INCARNATUS EST

“Et incarnatus est” and “Crucifixus” are handled as a single slow section for Type I chorus. The setting is reverent and hymnlike.

ET RESURREXIT

The tempo picks up briskly at “Et resurrexit” and at the words “Et ascendit in caelum”, the music also ascends. The music suddenly slows for the words “Vivos et mortuos” and then resumes brightly for “Cujus regni non erit finis“.

ET IN SPIRITUM SANCTUM

Then everything comes to a halt for “Et in spiritum sanctum“. an extended song for the bass soloist encompassing six leisurely lines of text. One would have to look a long time to find a song for bass more lovely than this. Perhaps Mozart was inspired to make amends for the awkward, uninspired bass aria to the same words in Leopold’s mass. More intriguing is the fact that Father Ignaz Parhamer, the Jesuit priest who oversaw the orphanage where “K139” was premiered, was also the youth organizer and spiritual advisor to St. Ursula Convent in Vienna, whose choir featured a nun, Mother Maria Johanna Nepomucena, with a resonant bass voice—not alto, bass!

What twelve-year-old genius could have resisted writing a mass for these nuns? In years to come, Mozart would specifically tailor opera arias for the particular range of his intended soloists. What if this was where he got the idea? The lowest note in this song (and indeed in the bass “section” of the chorus over the entire mass, which would have to have comprised solely this one nun) stops at the G below the C below middle C, which must surely have been her limit. In “K139”, composed for professional voices, and in the subsequent “K65”, written for Salzburg, the basses several times reach the low F. If “K49” was performed at the convent, no one ever made mention of it. But how perfect would that have been? It makes a great story anyway.

ET UNAM SANCTAM CATHOLICAM

The chorus return for “Et unam sanctam catholicam“, using the same tempo and theme fragment as “Et resurrexit”, as far as I can tell the only repeated theme in the Credo. The music slows dramatically for the word “mortuorum“, and, a moment before, the rhyming “peccatorum”.

ET VITAM VENTURI SAECULI

The final section is a Type II chorus on the words “Et vitam venturi saeculi“.

SANCTUS

“Sanctus” begins as a Type I chorus consisting of two short sections, “Sanctus” and “Pleni sunt caeli”. “Hosanna” follows after a brief pause and is a brief Type II chorus.

BENEDICTUS

“Benedictus” is for solo quartet with a gentle, flowing sound. The words are repeated four times: the first for soprano; the second for alto; the third for tenor and bass (since they have to share, they get twice as long); and the fourth for all four soloists. “Hosanna” returns as expected.

AGNUS DEI

The mass finishes strongly with a Type I chorus for “Agnus Dei”, with three impassioned cries of “Agnus Dei” alternating with two very quiet utterances of “Miserere nobis“.

DONA NOBIS PACEM

Though the mass is short, the final line, “Dona nobis pacem“, is still treated as a separate section and is light and lilting.

![]()